Rome: A History of Jewish Resilience

The Jewish diaspora has a worldwide reach, of course including Italy and its capital, Rome. Through centuries of hardships, the Jewish people have persevered for their right to exist in Rome by blending with the native culture as a means for survival.

The history of the Jewish community in Rome dates back to the time of the Roman Republic. According to Professor Jenn Lindsay of John Cabot University, the Jewish community was so well integrated in Rome that there's proof of a Jewish Senator in the 2nd Century BCE. It is the largest ethnic group to remain intact within the city of Rome since the time of the Empire, and is the largest and oldest Jewish community outside of Israel itself.

During the Middle Ages, the Jewish community in Rome came under the rule of the Papal State, incurring a tumultuous relationship between the two entities over the next thousand years as certain Popes were more lenient to the Jewish population than others. The most prominent result of the Popes' interaction with the Jewish community was the creation of the Roman Ghetto.

The Roman Ghetto was created by way of the Papal Bull, a letter the Pope issued, during the reign of Pope Paul IV in 1555. All Jews within the city, around two thousand at the time, were forced into a walled off community which had its gates locked at night. It forced the Jewish population into abject poverty and placed additional restrictions on them such as the inability to own property and the mandatory attendance of Catholic sermons on the Sabbath. The Ghetto remained until the Papal State was conquered by the Kingdom of Italy in 1870 and the requirement of Jews to live in the ghetto was abolished.

Shortly after the First World War, fascism rose in Italy under Benito Mussolini. At first, Fascist Italy did not promote anti-semitism, and some Jews reached high positions in Mussolini's regime (more on that below), until the passage of Race Laws in the late 1930s, targeting Jews by restricting their freedoms and livelihoods.

When Mussolini's regime fell in 1943, the Nazis occupied the northern half of the country. On October 16, 1943, the Nazi SS raided the ghetto and arrested over one thousand men, women and children. On the 18th, they were deported and sent to Auschwitz; only 16 of these deportees survived.

“The [Jewish] community in Rome was not only the oldest, but it was also the largest on the Italian peninsula and had this very symbiotic relationship first with the Roman emperors, obviously, and then after the fall of Rome in the 5th century of the Common Era, with the various popes of the Catholic Church,” explained professor Stanislao Pugliese, an educator of modern European history and Italian-American studies at Hofstra University, a specialist in Jewish experience specifically during the Nazi occupation in 1943. “Depending upon who was emperor or who was Pope at the time, conditions could be quite favorable, or they could be quite oppressive, but at no point are the Jews of Rome expelled from the city.”

With the long standing history of Jews in Rome, the culture has blended with Roman Catholics as a means for survival. This makes this corner of the diaspora one of the most unique in the world because this is one of the few parts where Jews didn’t face expulsion by the locals. Instead, they came together and merged with the local culture according to Pugliese, for a new language to emerge.

The Roman version of the Jewish dialect, as well as the Jewish community itself, developed in a unique, idiosyncratic way, according to, a professor of modern European history and Italian-American studies at Hofstra University, a specialist in Jewish experience specifically during the Nazi occupation in 1943.

Italian Jews combined the local language with Hebrew characters to make for Judeo-Italian, also known as Latino, where the language sounds similar to Italian but is written with Hebrew characters, a type of creole.

“What happens is that the Hebrew that the original Jews brought with them two thousand years ago when they were brought as slaves from Jerusalem eventually merge[d] with this Italian to create this unique language of Latino,” Pugliese explained.

“Judeo-Italian is an Italian dialect or, rather, a group of Italian dialects, varying from one part of Italy to another but containing a number of words of Hebrew origin and a few lexical items from other sources,” confirmed George Jochnowitz in a chapter of Pugliese’s book, The Most Ancient of Minorities: The Jews of Rome. “Most of the vocabulary is Italian; most of the grammatical rules may be found somewhere in the complex system of Italian dialects.”

The version spoken in Rome is idiosyncratic to Roman Jews, meaning that while Jews exist in other parts of Italy, their respective dialects differ slightly, whether in Venice, Florence, Palermo or other parts of Italy, Pugliese clarified.

This begs the question - with all of the Italian and Jewish immigrants that the United States saw in the late 1800s, why didn’t Latino come with them to the US?

The answer lies in the fact that as much as Roman Jews have been part of the fabric of the city of Rome, they weren’t always merged as one with its people, reflected mostly in their socioeconomic status compared to the local Romans and other Jewish groups. The Roman Jewish experience pales in comparison to that of Jews in major Italian cities in the northern half of Italy, and how generations of Jews lived there.

“Although the Roman-Jewish community was the largest In Italy, it was also the least educated and the poorest, so, the Italian Jews who tended to come to the United States, especially after the Racial Laws of 1938, they tended to be mostly Italian Jews from the north – from places like Milan or Torino or Florence or Venice - those were the Jews that had assimilated more than the Jews of Rome."

"Judeo-Italian is an Italian dialect or, rather, a group of Italian dialects, varying from one part of Italy to another but containing a number of words of Hebrew origin and a few lexical items from other sources."

It’s simple: the Jews of northern Italy leaned more middle class/bourgeoisie, with increased socioeconomic standings, meaning they had the means to attend university, possibly even study abroad, and very reasonably probably spoke more than one language, rather than speaking Hebrew or Latino.

There’s also the topic of food: Jewish cuisine differs greatly from the Roman food known worldwide. To quote The Daily Beast, all roads may lead to Rome, but the best route is via la gastronomía.

One of the most famous dishes from Rome’s Jewish Quarter is the baked artichoke, because it’s something that Romans themselves have been familiar with for centuries.

An issue that Roman Jews had to overcome was swine, as it is a staple in the typical Roman diet; prosciutto, capocollo, salami, mortadella, and other cold cuts are part of almost every Italian kitchen. Because swine is prohibited due to Kosher rules, as derived from scripture, Roman Jews adapted by using goose fat for cooking, as an example of finding their way around dietary restrictions.

"All roads may lead to Rome, but the best route is via la gastronomía."

Desserts in the Jewish Quarter in Rome

"Pizza Ebraica" Italian for "Jewish Pizza"

Close to the Interwar period, Dario Biocca, a historian and political science professor at John Cabot University, said that for the most part, Jews weren't in touch with their Jewish identity, characterized by absence of the practice of faith. With that, Jews were on equal footing with other Italians in the eyes of the lay, at least before the passage of the racial laws.

Biocca explained that while fascism was on the rise in Italy and the rest of Europe, Mussolini had Jews in the Italian government in the late 1930s, even during the height of anti-Jewish legislation.

"[Mussolini's lover] was a very prominent Jewish Venetian woman, who was dropped in 1938, but she was the person who polished Mussolini, made him into the head of state that could address foreign dignitaries, [and] told him that he needed to speak English, and so he learned English," Biocca explained.

Margherita Sarfatti. Mussolini's Jewish lover until 1938

Margherita Sarfatti. Mussolini's Jewish lover until 1938

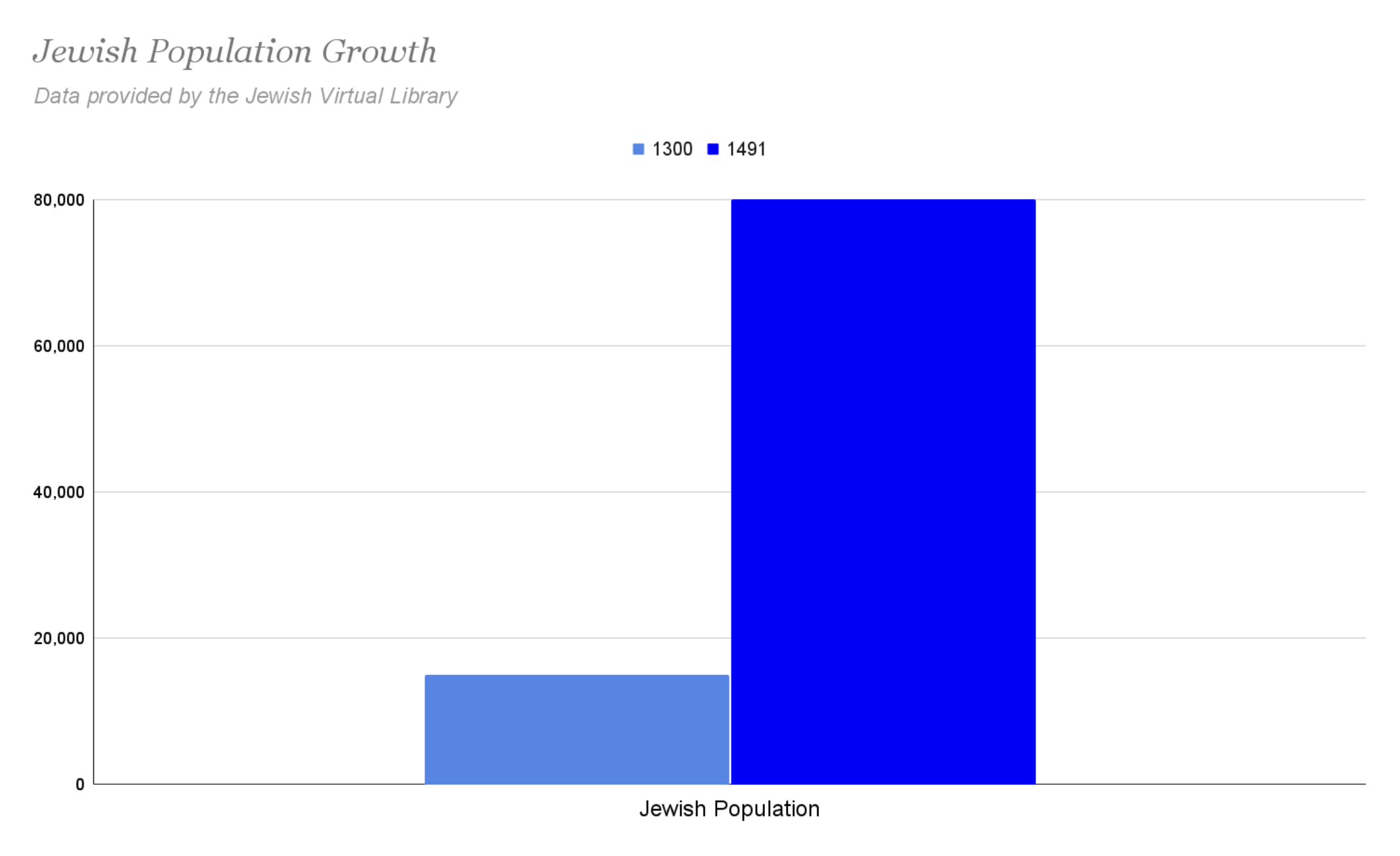

There are currently between 15,000-20,000 Jews in Rome, around half of the Jews in all of Italy.

To sum up the closeness of Roman Jews and non-Jews, Professor Lindsay invoked a common phrase from the Chief Rabbi of Rome, Riccardo di Segni:

“Roman Jews are Orthodox in identity, Reform in practice and Catholic in culture.”

While the two faiths differ, the ways of existing don’t.