Got Beef?: Understanding the Environmental Impacts of the Livestock Industry

As the global population continues to rise and the demand for animal protein in developing countries increases, producers and consumers around the world will have to address, and reconcile, the impacts of the livestock industry on the environment.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 14.5% of all global greenhouse gases come from the livestock sector. Livestock emissions alone produce 32 percent of all human-caused methane emissions.

Credit: Unsplash/ Oliver Augustijn

Credit: Unsplash/ Oliver Augustijn

The reason cattle, in particular, have such an outsized effect on producing greenhouse gases is because of a process known as enteric fermentation. Enteric fermentation is a digestive process among ruminants that produces methane while microorganisms break down molecules inside the animal.

Dr. J. Bret Bennington, chair of the Geology, Environment and Sustainability Department at Hofstra University, said methane is a “more effective greenhouse gas” than CO2, meaning it is better at trapping heat and therefore, has a greater impact on the atmosphere.

According to the Environmental Defense Fund, “Methane has more than 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide over the first 20 years after it reaches the atmosphere. Even though CO2 has a longer-lasting effect, methane sets the pace for warming in the near term.”

Ruminants are large hoofed herbivorous grazing mammals that are able to acquire nutrients from plant-based food through a process known as enteric fermentation. Credit: Unsplash/ Flash Dantz

Ruminants are large hoofed herbivorous grazing mammals that are able to acquire nutrients from plant-based food through a process known as enteric fermentation. Credit: Unsplash/ Flash Dantz

While it is significant that 14.5% of all greenhouse gases are attributed to livestock, Dr. Frank Mitloehner, an air quality specialist and the director of the CLEAR (Clarity and Leadership for Environmental Awareness and Research) center at UC Davis, noted that it is important to take this number with, “a grain of salt.”

Mitloehner explained that there is a large variability among the emission levels of individual countries and regions, which tells a story about the diverse challenges that each faces when addressing the issue of livestock and climate change.

A 2019 study published in Agricultural Systems, found that cattle were responsible for roughly 3.7% of the United State’s total greenhouse gas emissions. The study included emissions from the entirety of the cow’s lifespan: from birth to slaughter.

According to Mitloehner, in 1950 there were approximately 25 million dairy cattle in the United States and a human population of approximately 150 million. Today, the population of the United States has more than doubled, yet there are only nine million dairy cattle: the same number that there were in 1867.

This is possible due to advances in science and education over the years.

Mitloenher explained that more efficient insemination techniques, improved veterinary care, increased genetic merit of the feed crops and cattle themselves, as well as a better understanding of their nutritional needs, have allowed farmers to shrink their livestock herds. Therefore, much fewer cows are needed today to meet the same demand than once before.

Due to advances in science and education, the United States is able to meet consumer demands for dairy products using the same number of dairy cattle that there were in 1867. Credit: Unsplash/ Anseric Soete

Due to advances in science and education, the United States is able to meet consumer demands for dairy products using the same number of dairy cattle that there were in 1867. Credit: Unsplash/ Anseric Soete

Without access to the same levels of advanced technology, education, and resources, developing countries require many more cattle to produce the same amount of dairy and beef products than a country like the U.S. does

For example, in Africa, dairy cattle are responsible for producing 10% of enteric methane emissions worldwide, yet they only produce about 3.9% of the world’s milk supply.

In Paraguay, where the population of cattle is almost double its human population, greenhouse gas emissions from livestock are much higher. According to the USDA, in 2019, there were 13.8 million cattle in Paraguay and a human population of approximately 7 million.

70% of all greenhouse gases in Paraguay are a result of agriculture and out of that number, over 60% of the gases emitted were from enteric fermentation.

In addition to the inefficient methods of agricultural and livestock production resulting in larger herds, a reliance on beef for nutrition also contributes to the size of the herds and their methane emissions.

When it comes to countries like Paraguay, and regions like Southeast Asia and North Africa, where there are developing countries working to lift themselves out of poverty, whatever bit of disposable income people have goes to buying nutrient dense foods. That could mean eggs, beef, or a glass of milk, said Mitloehner.

In these regions, where food alternatives are scarce, livestock plays an important and necessary role in satisfying nutritional needs.

“Due to lack of arable land in many of the areas, farmers can not grow the same kinds of row crops that we rely so heavily on here in the United States,” said Mitloehner.

While plant-based diets are often sufficient in providing the proper balance of nutrients in places like the United States, due to the availability of diverse food and crops, developing countries do not have the same options.

“That’s a total luxury discussion. That is not a discussion in the real world outside of our bubble here,” said Mitloehner about the vegetarian and vegan movements that have gained traction among health and environmental enthusiasts in the West.

The IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change) estimates that about 80% of the global emissions from the livestock sector occur in developing countries because herds are so large.

While herds are bigger in these countries due to inefficient practices and nutritional dependencies, there are also other reasons that herds may be so large.

Dr. Frank Mitloehner explains another global issue that is creating major environmental impacts: food waste.

Dr. Frank Mitloehner explains another global issue that is creating major environmental impacts: food waste.

Idle animals are defined as those that eat, excrete, and produce emissions, but do not contribute to the food supply chain in any way.

In India, cattle are not consumed as beef due to religious reasons. As a result, after they are no longer productive in terms of making milk, they are often let loose: free to roam as they please.

According to Mitloehner, after the cattle are set free, they often live miserable lives, roaming around starving for food, and contracting diseases.

In the United States, most beef cattle go to slaughter at around 14-16 months of age and dairy cattle between 3-5 years of age. In countries like India however, cattle may live for up to 15-20 years, constantly producing methane.

Based on a study published by agricultural research expert, Masha Shahbandeh, as of 2020, India had 56,450 dairy cattle. This is the most of any other country in the world and more than double that of the European Union, which has the second most.

Besides religious reasons, idle cattle are also prominent in certain parts of the world, such as West Africa, where they are used for economic security and trade.

According to Mitloehner, in many small villages, the main purpose of cattle is to act as the “piggy bank” of the family or tribe. Herds of cattle, goats, and sheep are used to trade and act as a social security system of sorts. Therefore, they are kept alive for as long as possible, emitting greater amounts of methane over their lifetimes.

Idle cattle in countries such as India can live for as long as 20 years, emitting large amounts of methane into the air. Credit: Unsplash/ Bill Wegener.

Idle cattle in countries such as India can live for as long as 20 years, emitting large amounts of methane into the air. Credit: Unsplash/ Bill Wegener.

Davangere, Karnataka, India: An old Indian village man shepherd walking along with his sheeps on top of a hill during monsoon. Credit: Unsplash/ Manoj Kulkarni

Davangere, Karnataka, India: An old Indian village man shepherd walking along with his sheeps on top of a hill during monsoon. Credit: Unsplash/ Manoj Kulkarni

In developing nations large herds are seen as signs of wealth and are used to trade for good and services. Credit: Unsplash/ Amal Rajeev.

In developing nations large herds are seen as signs of wealth and are used to trade for good and services. Credit: Unsplash/ Amal Rajeev.

In addition to directly emitting methane into the air, the livestock industry has other indirect effects on the environment that contribute to global warming, such as deforestation.

In response to rising global food demands for animal sourced products like beef, Brazil has increased deforestation efforts in order to clear land for livestock and satisfy the demands, said Dr. Bennington.

The Amazon rainforest has suffered as a result.

Deforestation is one of the many consequences of livestock and agriculture. Credit: Unsplash/ Gryfynn M.

Deforestation is one of the many consequences of livestock and agriculture. Credit: Unsplash/ Gryfynn M.

According to the WWF, cattle ranching is the number one cause of deforestation in almost every Amazon country. In 2019 alone, deforestation in the Amazon increased by 30%.

“They don’t have to cut into their natural forest in order to produce beef,” said Mitloehner. “They have enough land.”

Instead, Mitloehner stressed the need for stricter regulations preventing deforestation for livestock use and focusing on improving land that has been overused through sustainable farming methods that can reverse soil degradation.

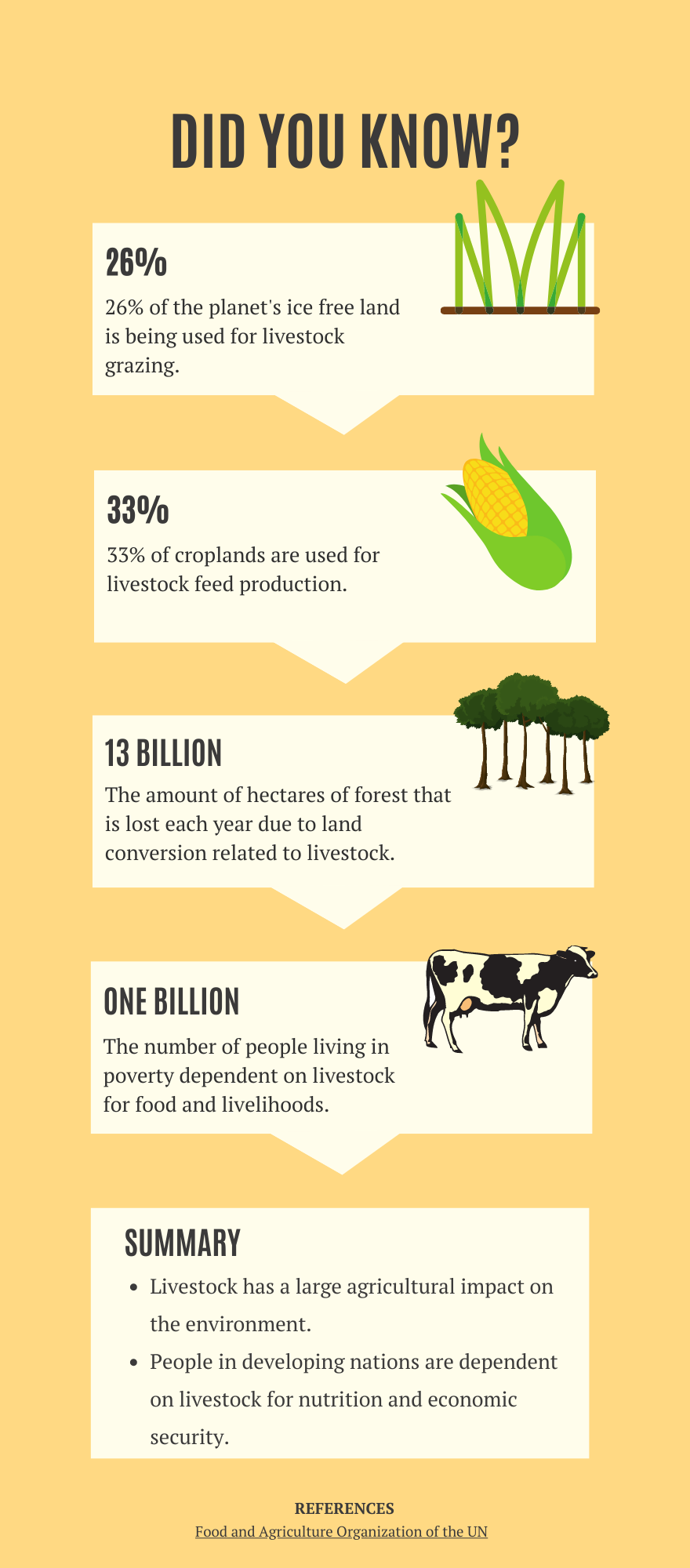

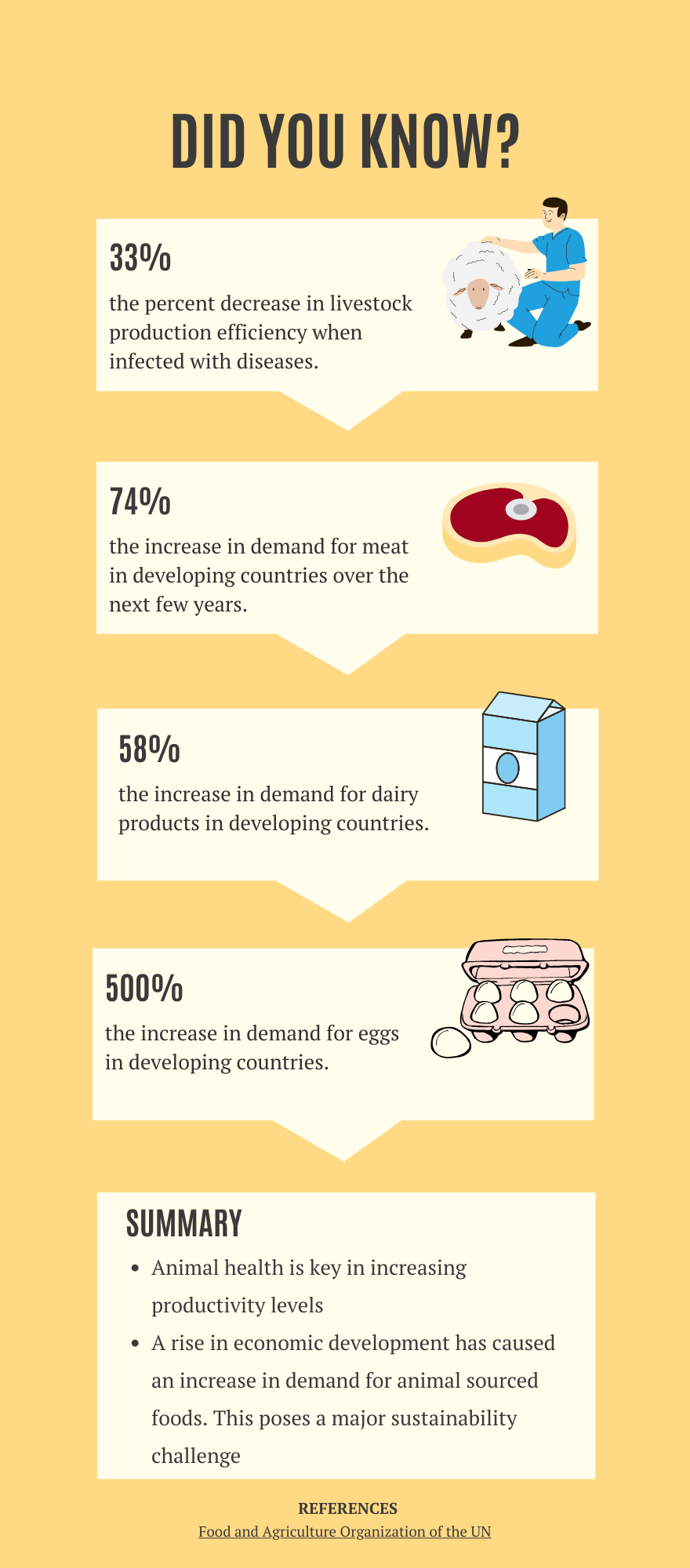

Data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN underlines key impacts of the livestock industry on the environment and developing countries.

Data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN underlines key impacts of the livestock industry on the environment and developing countries.

While one of the many proposed solutions to address the impacts of livestock on global warming is to stop eating meat, it’s not that simple.

With beef so ingrained in our everyday diets, changing our eating habits is “one of the harder things for people to do,” said Dr. Bennington.

“These are things that are very personal choices. They are made by people’s religious beliefs, by ethical beliefs, by all different kinds of beliefs,” said Dr. Mitloehner.

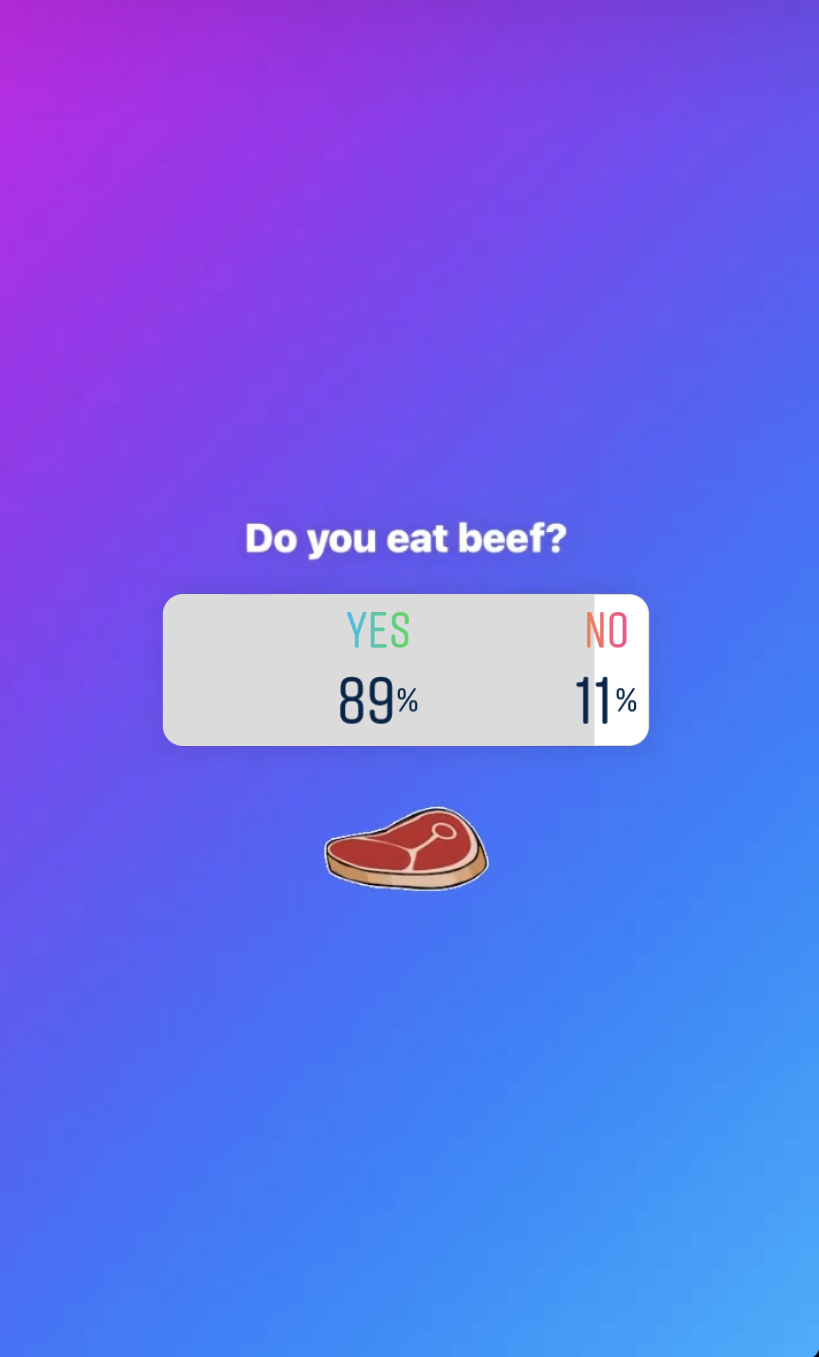

In an unofficial poll conducted on my instagram, 89% of respondents, or 164 out of the 185 participants, said they ate beef, and only 11% said they did not.

Furthermore, when asked how frequently they ate beef, 58% of respondents said they ate it one to two times a week, 34% said they ate it three to four times a week, and 8% said they ate it five times a week or more.

An unofficial poll conducted via Instagram highlights the heavy influence of beef in our diets.

An unofficial poll conducted via Instagram highlights the heavy influence of beef in our diets.

When participants who responded that they didn’t eat beef were asked why, responses ranged from taste, cost, environmental impacts, religion, animal rights, and inability due to disease.

Dr. Bennington, who views limiting meat consumption as important to lowering our environmental impact, offered various possible solutions to do so.

Some suggestions included consuming more imitation meat like beyond beef, finding ways to lower the cost of plant-based foods to make them more affordable, and continued research into lab grown meat. Bennington also suggested a gradual change in diet away from beef towards a Mediterranean diet, focused on plant-based protein, fish, and some poultry.

Contrary to Dr. Bennington, Dr. Mitloehner said he is skeptical of “the hype that people place around the impact of eating animal source foods and climate.”

“People will continue to make the choices of what they want to eat without anybody telling them,” said Mitloehner. “My job is not to convince people to change what they eat, but to help farmers improve their practices to reduce the environmental footprint of livestock.”